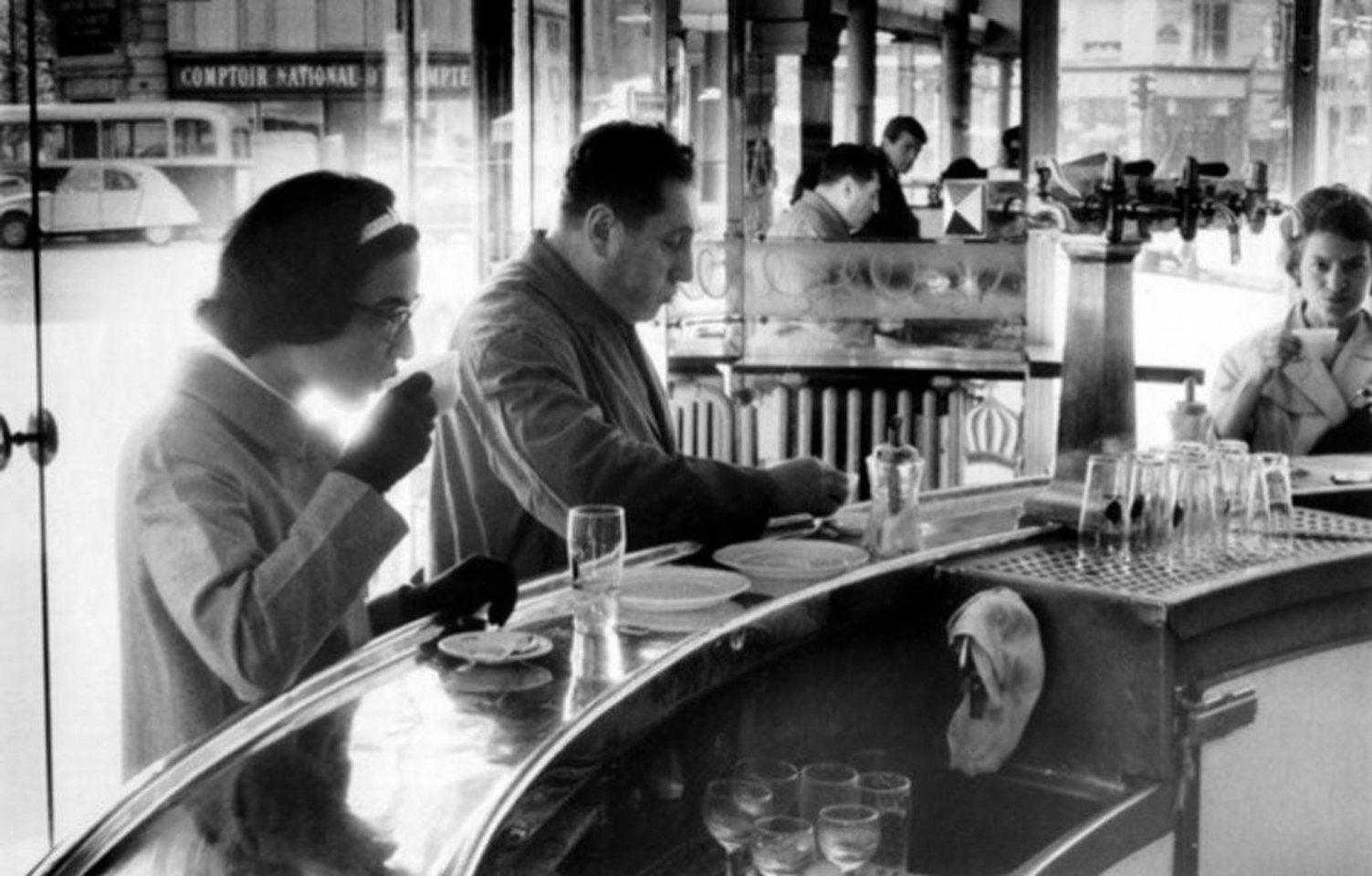

Michel Audiard could have made Bernard Blier say not so long ago"Because I like to tell you that for me Mr. Jacques with his coffee planted in Brazil in Roubaix and his Italian sock juice made in Grenoble ... ".

It's because the "p'tit noir de comptoir" haunts the imagination of all French people, feeds the scenes of all the old movies and inspires the best "brèves de comptoir". The "p'tit noir" is fundamentally patrimonial. What's wrong with my face... of black kid? Well, it has, at the same time, lead in the wing, and beautiful future in front of it, your mouth my black kid.

With the decline of the counter, the end of the coffee clops and hard-boiled eggs on the zinc, the rise of hygienism and the success of the capsule, the café, the place and its counter, a true parliament of the people, half smokehouse half drinking trough, has become depopulated and has turned into a clean and design place. If the fashion of the zinc and that of the noisy and crowded café pass, that of its sidekick, the "p'tit noir", persists, against all odds, for better or for worse. The change, sometimes at forced march, is on the way for a happy, good and tasty black coffee.

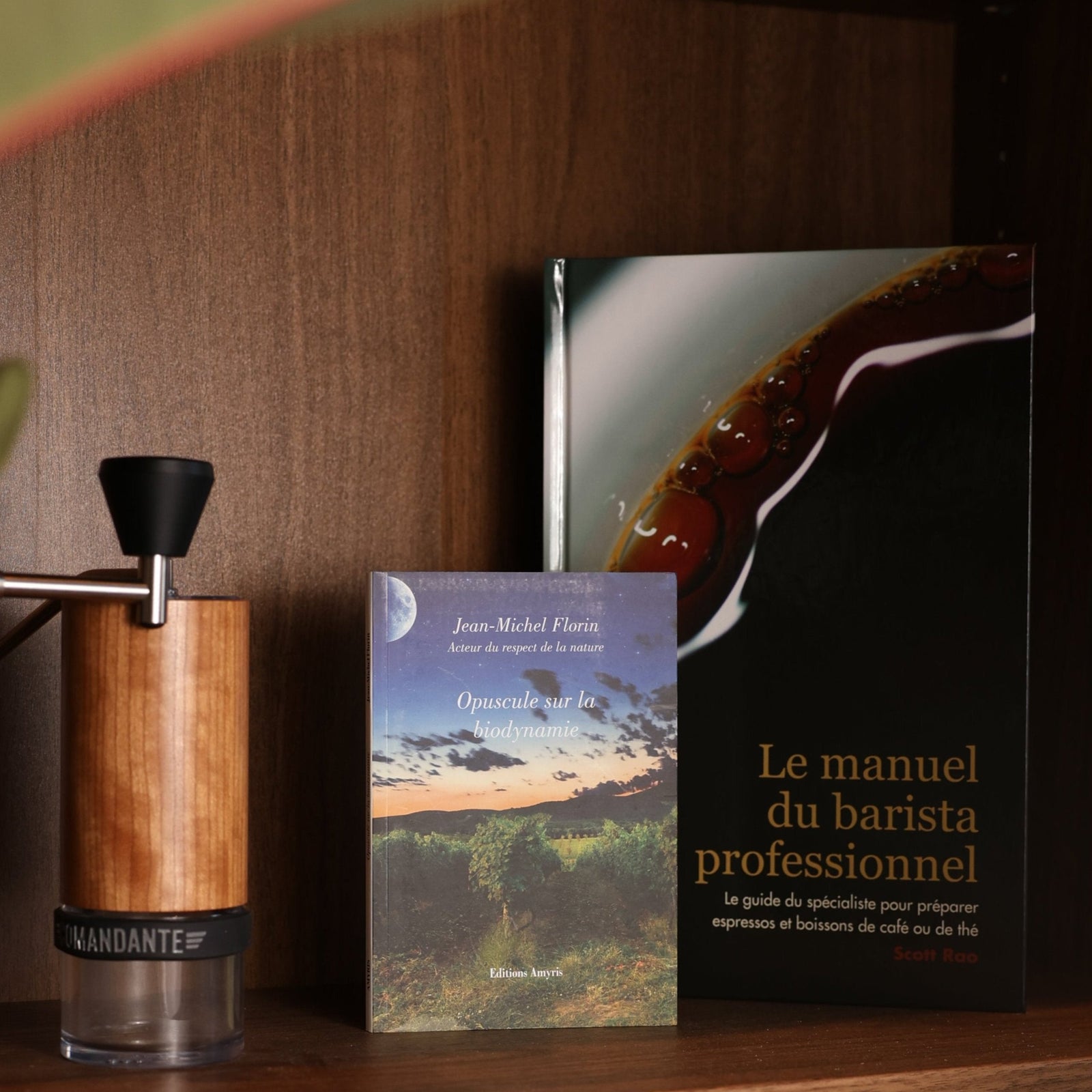

The p'tit noir was an art, a French art, that of a roasting called everywhere in the world with disdain, French Roast, that is to say a burnt and charred bean to black, even more than the Italian Roast, wet with water and oozing oil. The "Petit Noir" was the espresso, not the Italian espresso, that is to say, a coffee made quickly and badly, as long as it flows quickly, very quickly. Without foam, crema or color, the p'tit noir is sometimes (often?) pale.

Often bitter, woody, astringent and aqueous, the most refined concede notes of chocolate and hazelnut to him, the less careful, of rubber and ground. But what does it matter since it is sweetened and swallowed while smoking? The "p'tit noir" was more a prize than a drink, more a tic than a ritual, more an addiction than a pleasure, more a neglect than an offering. And if we don't know historically why it is called "le p'tit noir", the interpretations are multiple: dark black color, tire taste, burnt grain, it is certainly opposed to the Grand Cru and is far from this black liquor sung by Balzac and Voltaire.

It is that, without looking like it, the black kid also made politics. Coming from Black Africa when it was named as such, it is intimately linked to French colonization. Strongly robust because the Robusta, which is readily vilified today, grows in the plains and in abundance, in the warmth. The French therefore planted it everywhere in their West African colonies and for a long time supported the market, buying the less good qualities so that the best could be valued on the international market. Thus the Ivory Coast, Cameroon and many other countries were the world leaders in Robusta. This Robusta, known for its bitterness, its power and its vegetal character, was quickly adopted by the French, used to the bitter chicory since Napoleon. And their addiction was maintained by a highly regulated pricing system.

Like bread, coffee, a staple food, had a fixed price that prevented it from moving upmarket. However, if bread started its qualitative revolution more than 20 years ago, coffee's revolution has been a long time coming, but today, in 2018, it has definitely started and nothing can stop it. Restaurant owners, like all catering professionals, but also private individuals, now have the possibility of serving quality coffees, combining gourmet pleasure and aromatic complexity.

Gone are the extremes of the early adopters who were inclined towards an acidity that was thought to be opposed to the bitterness of Italian-style coffees, hello elegance and gourmandise. Gone are the disembodied names of coffee, hello the Grands Crus from terroirs and plantations. Coffee is finally entering the world of diversity, of geographical richness, of the nuance of vintages, of the links with such and such an appellation or even producers.

Anyone, as long as they buy it from the right roaster, can follow a plantation like one follows a winemaker. As a result, coffee lists are becoming possible and are constructed like a wine list, as at Yoann Conte's or at the Hostellerie de Plaisance with Ronan Kervarrec, playing with desserts as at Christophe Pelé's Clarence, or even being integrated into the kitchen as at Anne-Sophie Pic's, who cooks and serves it at the pedestal.

Coffee is no longer there by chance, but on the contrary, it participates in the identity of a place, a menu, a dish or a moment. It is always balanced, sapid and fresh, or on the contrary deep and tertiary, or fruity and fatty. The last bill of the meal then lasts for an hour in the customer's mouth. The restaurant owner, like the wait staff, regains his superb reputation by multiplying the associations of the coffee served, not with sugar and a glass of water, but with digestives, mignardises, and according to dusted rituals.

And it should not be believed that this quality coffee is reserved for a faithful elite of starred restaurateurs. Far from it. You can find this same attention to the product and this same approach to quality at the Café de la Nouvelle Mairie in Paris. The bistronomy is not left out, like at Les Canons in Nice, as well as the pizzerias like the Atelier Pizza in Corbeille. If you want to shake up prejudices, the "p'tit noir" now has carte blanche to offer pleasure, lots of pleasure. So, we can say it, the p'tit noir is dead, long live the p'tit noir.